NAUJHEEL, Uttar Pradesh: Suma Devi, a brick worker from Bihar’s Gaya, used the phrase “khat rahein hain” – ‘being worn down’ – to describe labouring at the kilns in Uttar Pradesh’s Mathura for the last 16 years.

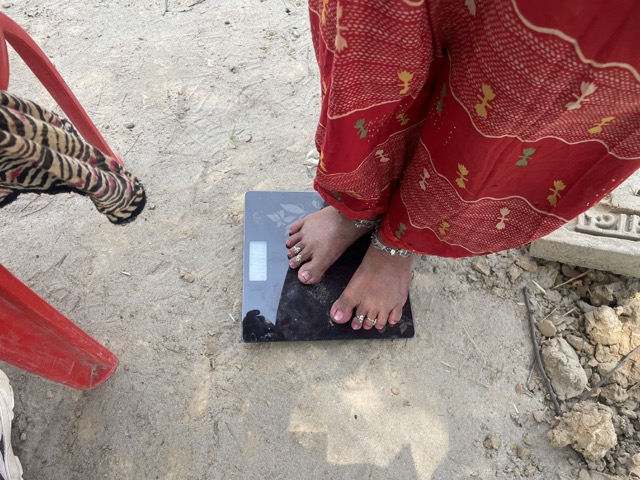

Suma, has a small frame and sunken eyes, traced her feeling of weakness and being sick to six years ago, when her daughter was born. Soon after she gave birth, Suma was diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB). She left her nine-month treatment midway to seek wage-work at brick kilns, 900 km from home.

Despite feeling ill, Suma started work at 8 am to start moulding bricks. In the breaks she took from moulding, she cooked for the family and swept the temporary brick hut that she and her husband built at the worksite. After sunset, which gave some reprieve from the summer heat, she began moulding bricks again, hoping to make at least 2,000 bricks till 1 am.

The brick kiln owner would pay her husband Rs 500 for every 1000 bricks Suma Devi’s family of three would jointly make.

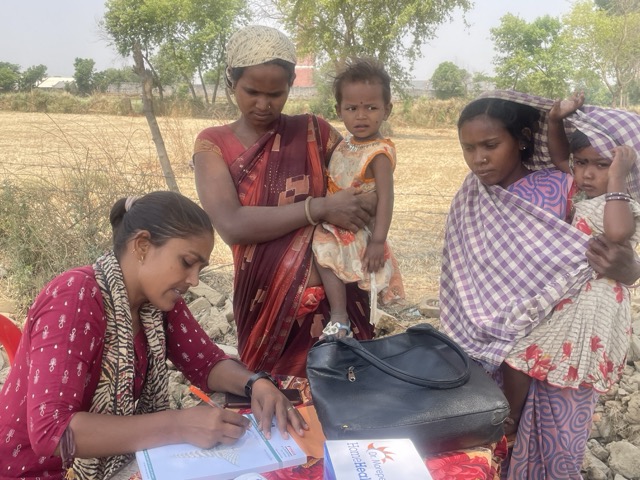

“The women usually spend less than six months in their village and their rights are curtailed,” said Lokesh S, executive director of NGO Centre for Education and Communication (CEC), that works on healthcare of migrant women and children in brick kilns.

But she could not access her food entitlements, as she is a seasonal migrant worker.

Asha Rawat, the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) – health workers in rural India – at the anganwadi (state-run child care centre) in Meerpur acknowledged the need to include the women migrant workers under the schemes, adding that she was unable to do so.

Health workers said they would respond if they receive a call from the kiln owners about a delivery about to happen, but could not actively seek out cases as they did among local residents.

“We tell the kiln accountant to send the pregnant women to Surir primary health center or Naujheel Community Health Center,” said Hemlata Chauhan, an auxiliary midwife in Naujheel.

While such directives have been consistently given to the brick kiln sector keeping the environment in mind and to ensure a transition from coal, there are no similar directives that mandate safeguarding of workers’ rights, particularly healthcare and protection from rising heat, labour rights campaigners said.

Every year, after the monsoon, millions of women – including pregnant women, their infants and children – travel long distances to seek work in brick kilns for nine months. The season usually starts in October and ends in early June, with kilns shutting down with the onset of the monsoon.

The women workers have no say in when or where to migrate, often moving during a pregnancy or despite an illness. They also don’t get the wages directly, which are paid to the male workers.

Heera Devi, a young mother, was anxious that her one-year-old son Kartik was weak and could not sit up at even 12 months of age. She said she usually lays him on a sheet on the earth when she works.